Abortion is legal in Namibia, but only if a woman is in danger or has been sexually abused. Activists are demanding reform

Members of the Voices for Choices and Rights Coalition march to the Zoo Park in Windhoek, Namibia, on July 18, to demand abortion reforms. Courtesy Hildegard TitusCNN — What do you do when your country is torn between decriminalizing abortion and maintaining its colonial abortion laws? Start a debate. That’s the idea being put forward by Esther Muinjangue, Namibia’s deputy minister of health and social services. The southern African nation has recently seen protests from both anti-abortion activists and abortion rights advocates. On June 25, Muinjangue, dressed in black, stood before the Namibian parliament and put forward a motion to debate the pros and cons of making on-demand abortions available to women in the country. “Whether or not legalized, abortion is a reality in our society and hence the need to debate on it, weigh the pros and cons, the advantages and disadvantages, in order for us as a country to make informed decisions,” she said during her televised appearance at the National Assembly. Muinjangue added that it was important for lawmakers to look into the reasons for abortions before making a decision to keep or repeal Namibia’s law on the conditions for terminating pregnancies. Abortion law Under Namibia’s Abortion and Sterilization Act of 1975, abortions are illegal for women and girls, except in cases involving incest, rape, or where the mother or child’s life is in danger. Namibia inherited the law from neighboring South Africa during apartheid, a system of legislation that segregated and discriminated against non-white South Africans. According to a report by the Guttmacher Institute, the law was put in place in 1975 to ensure that the white population in South Africa would continue to procreate amid fears that the black population was growing too quickly. Even though South Africa changed its law in 1996, two years after the end of the apartheid, Namibia continued to uphold the criminalization of abortions. And as Muinjangue and her colleagues in the Namibian parliament continue to debate whether or not they want to keep upholding this 45-year-old law, feminists and activists in the country are calling it discriminatory and lobbying for it to be repealed. “These laws are truly outdated and the countries we inherited those laws from have long changed theirs. Meanwhile, we still continue to keep ours,” Naisola Likimani told CNN. Likimani is the lead of the SheDecides Support Unit. She Decides is a global gender rights movement which speaks out for the right of women and girls to make decisions about their bodies. Given the risk involved in pregnancy and childbirth, she said, women should be given the chance to decide if they want to subject their bodies to the possible dangers that come with pregnancy. Approximately 810 women died every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth in 2017, according to the World Health Organization. In the same year, Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 86% of the estimated deaths of women during pregnancy. “Giving birth is a life and death situation for many women. You are putting your body at risk when you decide to carry a pregnancy. So, you should really be the one to say whether or not you want to carry it,” Likimani said. Petitions and protests Thousands of Namibians have signed a petition calling for a reform of the abortion law. The petition, posted in June by Beauty Boois, a Namibian feminist and psychologist, currently has more than 61,000 signatures in support of legalizing abortion. “We hope that this petition results in the legalization of abortion in Namibia so that Namibian women can take full ownership and practice autonomy over their own bodies,” Boois wrote in the petition. The petition was signed by multiple organizations and womens’ groups including Out-Right Namibia, the Young Feminist Movement of Namibia, and Power Pad Girls. It also resulted in protests on July 18 that included hundreds of feminists and activists demanding that sexual and reproductive rights of women be upheld. Some Namibians in the diaspora also joined the protests online, showing solidarity by using the hashtag #LegalizeAbortionNA. “Part of our demand during the protest was access to wholistic reproductive justice care for Namibian women. We want access to on-demand abortion for anyone from the age of 10,” Ndiilokelwa Nthengwe told CNN. Nthengwe is the communications officer for the Namibia chapter of humans rights organization, Outright Action International, and one of the protesters fighting for sexual reproductive health and rights for women in Namibia. Ndiilokelwa Nthengwe is a feminist and co-founder of the Voices for Choices and Rights Coalition. Courtesy Hildegard Titus Other African countries, including Mozambique and Ethiopia, have relaxed abortion laws that allow girls under the age of 18 to seek abortions, and pregnancies of up to 16 weeks to be terminated. In South Africa, a woman of any age can get an abortion on request with no reason given if she is less than 13 weeks pregnant. In addition to wanting similar opportunities for women in Namibia, Nthengwe said activists want the government to make provision for post-abortion care in the country. “We want a new bill that not only prioritizes abortions but also provides access to comprehensive sexual health education. We sent our demands and research to the parliament, to politicians as well. But we haven’t gotten a response yet,” she said. Unsafe abortions One of the major disadvantages of failing to reform abortion laws is that it can lead women having unsafe abortions said Dr. Bernard Haufiku, Namibia’s former minister of health and social services. Illegal abortions are often carried out secretly in the backrooms of doctors or by unauthorized people, which can be painful and dangerous to women, according to Haufiku. Haufiku, who is a medical doctor, told CNN that many women have died trying to circumvent the law procuring backstreet abortions and authorities owe it to take action that can prevent such deaths. Abortion rights activists demonstrate in Windhoek, Namibia, on July 18. Courtesy Hildegard Titus “We (would) rather abolish backstreet abortions that have taken many lives in Namibia. It is not about pushing abortion, it’s about saving lives of women who will pursue backstreet abortions due to socioeconomic reasons especially if

#ShutItAllDownNamibia

Six months after Namibia celebrated the thirtieth anniversary of her independence from South Africa in March 2020, the country is on fire. For the past two weeks, hundreds of Namibian activists, students, working youth, and artists have taken to the streets of Windhoek and other towns. The protests started on 7 October after the body of a young woman was found murdered in the port city of Walvis Bay. Twenty-two-year old Shannon Wasserfall had been missing since April of this year. A New Generation of Youth Activists This young generation, triggered by the scourges of femicide and gender-based violence, is tired of living in a violent society. One of their major rallying cries has been #OnsIsMoeg (Afrikaans for “We are tired”), along with, significantly, #ShutItAllDownNamibia. The hashtag expresses their aim of disrupting business-as-usual in a situation of crisis. Protesters have been marching on various ministries and demanding the resignation of Namibia’s Minister of Gender Equality, Poverty Eradication and Social Welfare, Doreen Sioka. Anti- sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) activists forwarded a petition to parliament, demanding political action to address femicide, rape, and sexual abuse. In response, Prime Minister Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila issued a statement saying that the protesters’ petition would receive “priority” and that the government was “in full agreement” that the high incidence of sexual and gender-based violence “cannot be allowed to continue”. Young activists and established gender equality advocacy groups such as Sister Namibia have pointed out, however, that the government promulgated two national plans of action against SGBV before, in 2016 and 2018, of which little has been implemented. “The system has failed us” read one of the hard-hitting placards a young woman held up at one of the ongoing protests in Windhoek. Drawing on Cardi B’s recent hit single, “WAP”, young protesters taunted the police force with radical hip-hop moves inspired by the song. During one of the early marches on Saturday, 10 October, protesters were forced to scatter in central Windhoek after security forces threw tear gas and shot rubber bullets at them. Twenty-six activists were detained, although charges against them were later dropped. One of the arrested protesters said that the dropped charges were a bittersweet moment for the movement, as the activists did not have the opportunity to expose the police’s abuse of power. This incident caused much concern. Minister of Home Affairs, Frans Kapofi, eventually apologized for the police brutality during a meeting on 23 October with youth activists to discuss issues of gender-based violence. The recent protests are the latest in a series of actions, as young Namibians have taken to the streets in growing numbers over the past few months. In early June, following the murder of George Floyd in the United States, protests under the Black Lives Matter banner were also organized in Windhoek. At the time, Namibia’s BLM activists focused on a statue near the Windhoek municipality building of German colonial officer Curt von François, deemed the “founder” of Windhoek in colonial historiography. They demanded the removal of the statue with a widely circulated petition under the hashtag #CurtMustGo. Alongside this local activism against colonial iconography, the Namibian BLM protesters addressed other pressing demands concerning structural racism and social inequality. They called for an end to police brutality during the COVID-19 lockdown, then in full force, which had hit impoverished urban areas hard. Speakers also insisted that the long-standing issues of gender-based violence had to be addressed, not least because they had been exacerbated during the hard lockdown. A few weeks later, in mid-July, protesters took to the streets again. This time they demanded the legalization of abortion and expansion of women’s reproductive health rights. The pro-choice action was organised by a newly-formed alliance known as Voices for Choices and Rights Coalition (VCRC), which had by then already collected 60,000 signatures (quite a large amount given that Namibia’s population is only 2.5 million) calling for the right to safe abortion and abolishing the country’s Abortion and Sterilisation Act of 1975, a legal legacy of South African colonization. The series of connected protests against coloniality and structural violence have galvanized growing numbers of young Namibians to reclaim the streets, marching and dancing and unleashing incredible creative energy with their performances. Social media users from across the African continent have posted on Twitter and Instagram in solidarity, linking the Namibian protests to political actions happening elsewhere on the continent, from Nigeria in the West to Zimbabwe in Southern Africa. This is no longer just a protest about sexual and gender-based violence. Thirty years after the end of apartheid colonialism, a new generation of young Namibians are again speaking up. Challenging the vestiges of coloniality in the country, they follow in the footsteps of an earlier generation of activists who made enormous contributions to the political (although socially incomplete) liberation of Namibia in the 1980s. In the light of the new generation of Namibian activists forcefully asking penetrating questions and engaging in collective action over the past few years, culminating in the 2020 protests, the history of the popular urban revolt of the 1980s has become particularly significant once again. The Vibrant Past: Anti-Discrimination Protests In the 1980s In the 1980s, social and political developments in Windhoek and other towns of central and southern Namibia critically challenged the politics of the nationalist struggle. From 1983 onwards, residents protested against the price of electricity and formed street committees in several towns. A popular revolt against poor living conditions and the oppression under apartheid colonialism was staged by residents’ associations, and movements of workers, students, and women, and was also reflected in an emerging alternative press. In 1987, 29 community-based organizations were listed, ranging from residents’ associations to women’s, church, education, and health groups. These social movements took up people’s day-to-day concerns under conditions of worsening poverty after the (partial) abolition of influx control laws led to accelerated urbanization, and an economic recession set in towards the end of the 1970s. The crisis hit urban Namibia at about the same time that the South

Abortion is lawful in Namibia, however just if a lady is at serious risk or has been explicitly mishandled. Activists are requesting change

Namibia celebrated the thirtieth anniversary of its independence from South Africa in March 2020, today the country is on fire. Heike Becker writes about the Namibian activists, students, working youth, and artists who have taken to the streets of Windhoek and other towns in the past few weeks. By Heike Becker Six months after Namibia celebrated the 30th anniversary of her independence from South Africa in March 2020, the country is on fire. For the past three weeks Namibian activists, students, working youth and artists have been protesting in the streets of Windhoek and some other towns. Hundreds of young people were driven into street action from 7 October after the body of a young woman was found murdered in the harbour city of Walvis Bay. Twenty-two year old Shannon Wasserfall had been missing since April this year. The scourges of femicide and gender-based violence triggered the current protests of a young generation who are tired of living in a violent society. #OnsIsMoeg (Afrikaans: “We are tired”) has been one of their social media hashtags, the other one is, significantly: #ShutItAllDownNamibia. They thus express their aim of disrupting business-as-usual in a situation of crisis. Protesters have been marching on various ministries and demanded the resignation of Namibia’s Minister of Gender Equality, Poverty Eradication and Social Welfare, Doreen Sioka. Anti sexual gender based violence (SGBV) activists forwarded a petition to parliament, demanding political action to address femicide, rape and sexual abuse. In response Prime Minister Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila issued a statement, which said the protesters’ petition would receive “priority” and that the government was “in full agreement” that the high incidence of sexual and gender-based violence “cannot be allowed to continue”. Young activists and established gender equality advocacy groups such as SISTER NAMIBIA have pointed out however that the government had promulgated two national plans of action against SGBV before, in 2016 and 2018, but little had been implemented. “The system has failed us” read one of the hard-hitting placards a young woman held up at one of the ongoing protests in Windhoek. With radical WAP inspired hip hop moves (drawing on Cardi B’s recent hit single WAP – wet-ass pussy) young protesters taunted the police force. During one of the early marches on Saturday, 10 October, protesters had to scatter in central Windhoek after security forces threw tear gas and shot rubber bullets at them. Twenty-six activists were detained, although the charges against them were later dropped. One of the arrested protesters said that the dropped charges were a bittersweet moment for the movement as the activists did not have the opportunity to expose the police’s abuse of power (The Namibian, 13 October 2020). The protests against sexual gender based violence are the latest in a series of protest action. In increasing numbers young Namibians have taken to the streets time and again over the past few months. In early June, following the murder of George Floyd in the US, protests under the Black Lives Matter banner were organised in Windhoek too. At the time Namibia’s BLM activists focused on a statue near the Windhoek municipality of German colonial-era officer Curt von François, deemed the “founder” of Windhoek in colonial historiography. They demanded the removal of the statue with a widely circulated petition under the hashtag #CurtMustGo. Along with this local impression of activism against colonial iconography, the Namibian BLM protesters addressed other pressing demands of structural racism and social inequality. They called for an end to police brutality during the Covid-19 lockdown, then in full force, which had hit the impoverished urban areas hard. Speakers also insisted that the long-standing issues of gender-based violence had to be addressed, not in the least because they had become exacerbated during the hard lockdown. A few weeks later, in mid-July, protesters took to the streets again. This time around they demanded the legalisation of abortion and expansion of women’s reproductive health rights. The pro-choice action was organised by a newly-formed alliance Voices for Choices and Rights Coalition (VCRC), which had by then already collected 60,000 signatures (note: Namibia’s population is only 2.5 million) to a petition that called for the right to safe abortion and the abolition of the country’s Abortion and Sterilisation Act of 1975, a South African legal colonial legacy. The series of connected protests against coloniality and structural violence have brought increasing numbers of young Namibians out. They have claimed the streets, have marched and danced and unleashed incredible creative energy in performances. Social media users from across the African continent have posted on twitter and instagram in solidarity, linking the Namibian protests to political action happening elsewhere on the continent, from Nigeria in the West to Zimbabwe in Southern Africa. This is no longer just a protest about sexual gender-based violence. Thirty years after the end of apartheid colonialism, a new generation of young Namibians are again speaking up. Challenging the vestiges of coloniality in the country, they follow in the footsteps of an earlier generation of young activists who made enormous contributions to the political, though socially incomplete liberation of Namibia in the 1980s. In the light of the new generation of Namibian activists who have been forcefully asking penetrating questions and engaging in collective action over the past few years, culminating in the 2020 protests, the history of the popular urban revolt of the 1980s has become particularly significant again. In the 1980s, social and political developments in Windhoek and other towns of central and southern Namibia critically challenged the politics of the nationalist struggle. From 1983 onwards residents protested against the price of electricity and formed street committees in several towns; a popular revolt against poor living conditions and the oppression under apartheid colonialism was staged by residents’ associations, and movements of workers, students and women, and significantly reflected in an emerging alternative press. In 1987 twenty-nine community-based organisations were listed, ranging from residents’ associations to women’s, church, education and health groups. The social movements took up people’s day-to-day concerns under the conditions of worsening poverty after the (partial) abolition

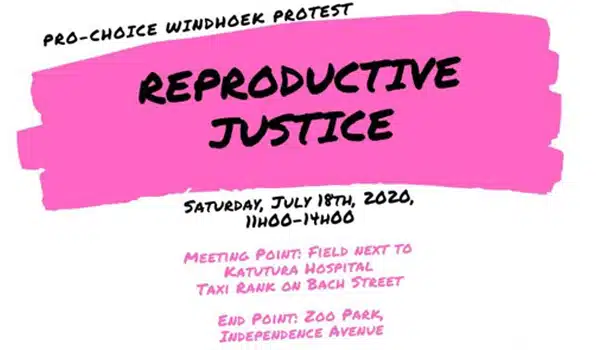

NAMIBIA – Voices for Choices & Rights Coalition: In-person and online protest to demand abortion rights

Apetition addressed to the Honorable Dr Kalumbi Shangula, Minister of Health and Social Services, has already garnered 61,310 signatures. PLEASE SIGN TOO!! Here are some terrific video and visual pictures from the march in Windhoek, posted on social media by the main organiser, Voices for Choices & Rights Coalition @LegalizeAbortionNA: This VIDEO at @JanaMariNam features the range of placards and the voice of the activist leading chants as shown here, as the marchers go by: Next is a video overview of the marchers, showing how long it is, taken from above: Here are some stills from @LegalizeNA: @JulianaPersaud @samntelamo

Hello world!

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!